Debt Dynamics and Financial Stability in Africa

June 6, 2023

African countries were severely hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, which quickly drove the continent into its worst recession in fifty years. According to the 2022 African Development Bank African Economic Outlook (AEO), real GDP declined by -1.5% in 2020 compared to growth of 3.3% in 2019. Africa has recovered quickly from the recession, but this has not translated into favorable debt prospects for many countries. To make a challenging situation even worse, the Russia/Ukraine crisis has cast further doubt on prospects for debt sustainability in Africa. The international community has reacted to these events by putting in place a Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI). To address debt needs further, the G20 has introduced a Common Framework to facilitate debt relief, including from the private sector. These two initiatives have not proven sufficient to meet Africa’s debt challenge.

Africa thus would benefit from the introduction of a financial stability mechanism that would work with countries to put their finances back on a sustainable path and help ensure market access. Section 1 of this paper details Africa’s new wave of debt crises since 2010. Section 2 discusses the new debt resolution framework and its limitations. The paper then concludes by setting out the rationale for a new financial stability mechanism.

Section 1: Africa’s New Wave of Debt Crises

Over the past decade, a new wave of debt accumulation has been one of Africa’s most significant economic and financial developments. This second wave of indebtedness appears more dramatic than the first wave, which occurred from 1970 to 2010.

1.1. High-Speed Debt Accumulation Since 2010

Reflecting the combination of debt cancellation under the Enhanced Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative, plus prudent fiscal policies and improved management of public finances, Africa’s debt declined dramatically from a peak of 100% of GDP in 2000 to a thirty-year record low of 38% of GDP in 2010.

Since then, this trend has reversed at high speed. Total debt to GDP increased by more than 24 percentage points in less than a decade, from 38.4% in 2010 to 62.5% in 2019. For North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa, debt more than doubled in a decade. The underlying causes of this new wave of indebtedness are procyclical fiscal policies in a context of a commodity- price super-cycle, large flows of private resources, and an abundance of Chinese financing.

1.2 Changing Structure of the Debt

There have been several notable developments in the changing structure of the debt in this current wave of indebtedness. First, the debt has shifted away from financing via traditional multilateral and Paris Club creditors, which until 2010 were Africa’s main creditors.

The share of multilateral debt in Africa’s total external debt has remained relatively stable over the past two decades. In 2019, 31% of Africa’s external debt obligations was owed to multilateral creditors, almost the same as the level in 2000.

The share of bilateral debt in total external debt, on the other hand, has fallen by almost half in the last two decades. In 2000, bilateral lenders, mostly Paris Club members, accounted for 52% of Africa’s external debt stock, but by the end of 2019, this had fallen to 27%. China—a non-Paris Club creditor—has become the second single largest creditor to African economies, ranking only behind capital-market bondholders, who themselves have taken on a much larger financing role than they did historically.

Second, while debt owed to public-sector creditors dominated the first wave of African indebtedness, private-sector debt has become the dominant component of African debt. The share of commercial creditors (bondholders and commercial banks) has more than doubled in the last two decades. In 2000, only 17% of Africa’s external debt was owed to commercial banks and private bondholders. This share has grown quickly since, and now accounts for 40% of total debt. Third and perhaps most dramatic is the change in the key role of bond financing. By the end of August 2020, 21 African countries had gained access to international capital markets and had issued more than 125 Eurobonds valued at over $155 billion. This compares to only three countries in 2001.

Finally, local currency debt issuance has increased since 2019, and now accounts for close to 40% of total debt stock, although this trend has been concentrated in specific countries.

1.3 Debt Vulnerabilities and Gloomy Prospects

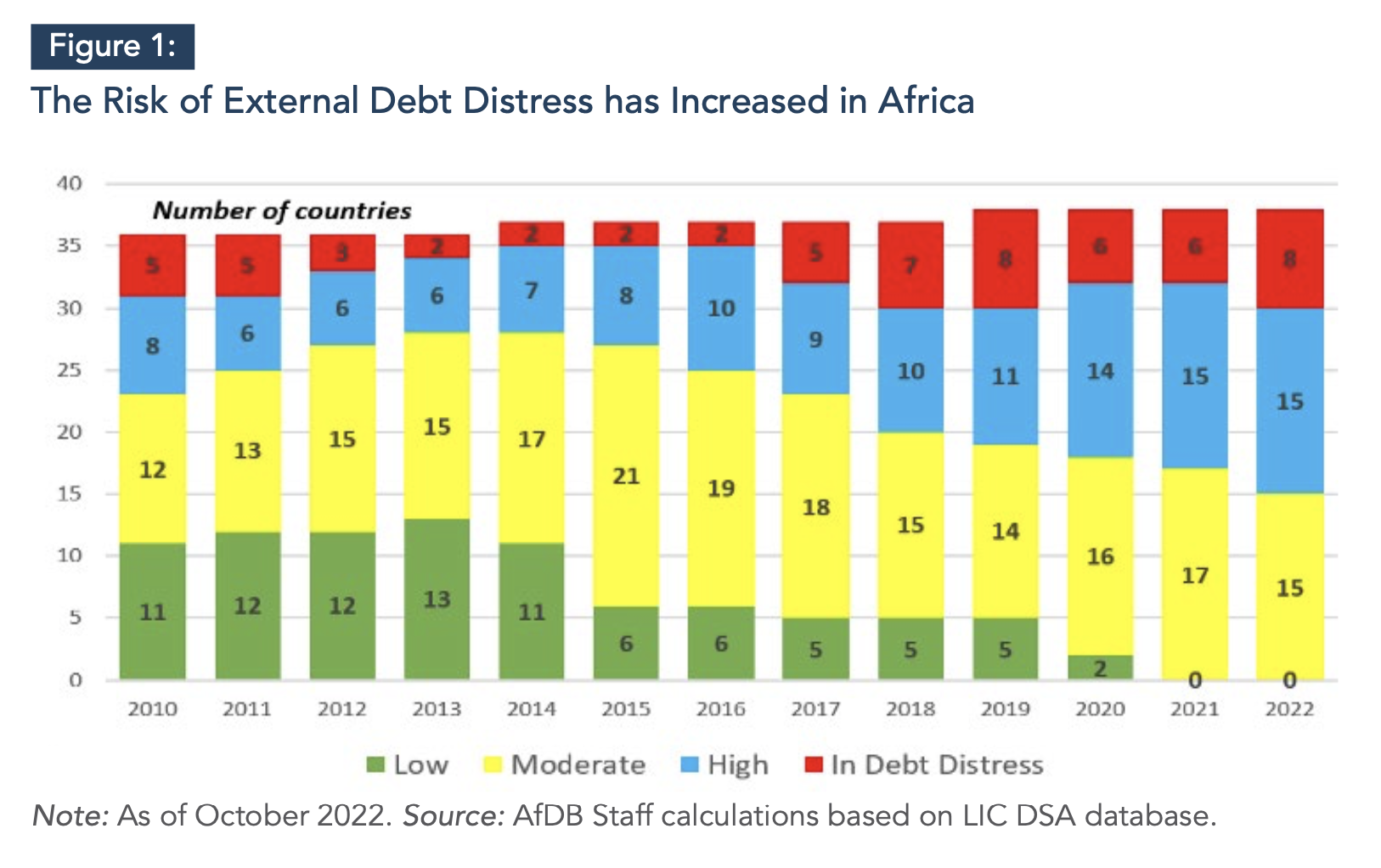

The ongoing wave of indebtedness has been accompanied by an unprecedented rise in debt vulnerability in particular for low-income countries (LICs). In 2010, only 13 African LICs were either in high risk or in debt distress. That number had increased to 23 countries as of October 2022. Also, the number of countries at high risk of debt distress has nearly doubled from eight in 2010 to 15 in 2021, and as shown in Figure 1, there is no longer any African LIC with low external debt distress.

Most African LICs missed the opportunity granted by debt cancellation under the HIPC initiative to take decisive control over their indebtedness. Many African LICs have failed to sustain policies to put their economies on a path of sustainable debt levels and robust growth. One contributing factor may have been the commodity price super-cycle, which ended in 2014-15 and didn’t favor the implementation of prudent fiscal policies. The belief that commodity prices would be permanently high favored pro-cyclical fiscal policies.

The downgrading of many African countries reflects these emerging debt vulnerabilities. Between 2018 and 2020, 11 countries were downgraded, three were upgraded, and seven retained their ratings.

Increasing interest rates and the corresponding rise in interest costs have aggravated debt vulnerabilities in recent years. The interest burden has increased steadily over the decade, rising from 8% of revenue in 2010 to more than 18% in 2019.

High interest rates and relatively low and declining public revenues have created short-term uncertainty over the ability of African countries to pay debt-service costs. If countries miss maturing payments, this could lead to widespread defaults and restructuring agreements.

The shift towards borrowing from non-Paris Club lenders and commercial creditors has led to greater refinancing risks. The surge since 2013-2014 in the issuance of 10-year Eurobonds by many African countries has caused a bunching of sovereign debt that will become due in 2024 and 2025. This bunching in maturities elevates risks of debt distress.1

Greater exchange rate and rollover risks are associated with increased reliance on external commercial financing. Depreciation of local currencies in turn can cause upward revaluations of a country’s debt, and also makes debt service in the foreign currency more expensive. Currency-mismatch exposure explains a significant portion of the deteriorating debt dynamics in many countries.

Debt vulnerabilities also have been aggravated by expanding contingent liabilities associated with increasing public-private partnerships, and related explicit or implicit government guarantees. Moreover, the ‘race to seniority’ in debt collateralization has become an important risk factor for borrowers. Creditors seek to collateralize their debt using strategic assets, creating an uneven hierarchy of creditors that could complicate debt-resolution negotiations.

This risk is compounded by limited reporting on the debt obligations of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in sectors with systemic importance, including energy, finance, transport, and telecommunications. These hidden debts, when eventually revealed, can worsen a country’s overall debt outlook. One additional problem is the lack of full transparency on loan terms. Most of the countries currently in debt distress or at high risk of debt distress have high exposure to Chinese loans and oil-backed loans from commodity traders, and the details of these obligations are often hidden. 2

The current Russia/Ukraine war will lead African oil-importing countries to experience wider fiscal and trade deficits and more inflation pressures. Economies that are exporters of oil and gas will benefit from higher prices, but in general, African countries may suffer from higher energy and food prices, and from reduced tourism because of the pandemic and economic conditions. This adds to expectations that debt accumulation in the continent will accelerate in the coming years.

Notwithstanding these gloomy prospects, Africa has vast reserves of minerals, energy resources, and arable land, and hosts the youngest population in the world. Making sure that the African continent emerges from this crisis stronger and better able to develop sustainably is, therefore, in the interest of the global community.

Section 2: Debt Resolution Architecture and its Limitations

The international community has so far failed to establish a consistent formal architecture for debt resolution. Debt resolution initiatives have thus been disorderly and mainly driven by the goodwill of creditors. As a result, debt relief has been ad hoc and has not produced the intended outcomes, often delivering too little and too late.

2.1 Late, Disorderly, and Protracted Debt Resolution and its Consequences

Debt resolution has historically come late, and has been disorderly and protracted. Securing the participation of non-Paris Club official bilateral and private commercial creditors has always been a challenge. Lack of coordinated action has left African countries to negotiate debt relief alone with little success.

While many African LICs were in debt distress in the late 1980s, it took more than a decade before the international community reacted with the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative in 1996, and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative in 2005. Moreover, the implementation of these efforts was protracted, lasting over two decades. 3

The absence of a formal international debt resolution framework has led the international community to fall back on temporary and relatively uncoordinated debt-relief initiatives. The Group of 20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) and Common Framework have been initiated in that context.

2.2 The G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative and its Limitations

In the face of the pandemic, the G20 launched the DSSI for low-income countries in April 2020, subsequently extending it to December 2021. In the absence of such support, debt- service burdens would have been higher, posing serious threats to the recovery.

While DSSI has alleviated the immediate liquidity pressures facing African economies, savings from the DSSI for all 38 eligible African countries are estimated at little more than $13 billion, ranging from $4.5 million in Liberia to $2.9 billion in Angola. 4

In other words, the savings from the moratorium represented only 24.5% of total projected debt-service payments of African countries for 2020, and 40.1% for 2021.

The DSSI lacked private sector participation, in part because comparable treatment of private creditors was encouraged but not required. As of April 2022, only one private creditor took part in restructurings, despite the G20’s repeated calls to private creditors to join the initiative on comparable terms. 5

2.3 The G20 Common Framework for debt treatments and its limitations

Unsustainable debt levels in many low-income countries led the G20 to agree in November 2020 on a Common Framework for debt treatment. The Common Framework aims to deal with insolvency and protracted liquidity problems in DSSI-eligible countries. It provides debt relief consistent with a debtor’s capacity to pay and maintain essential spending needs.

The main purpose of the Common Framework is to bring bilateral creditors, non-members of Paris Club such as China, and the private sector into the debt-restructuring process.

More than a year after its inception, however, the Common Framework has yet to deliver its promised outcomes. China has shown little willingness to participate fully in the initiative, and private creditors have so far not joined.

The Common Framework process itself is moving slowly. Incentives for private creditors to join are not strong enough and it is unclear how comparable treatment will be enforced. Moreover, there is no agreement among G20 creditors themselves on how to address a country’s full debt picture, which has raised concerns about the effort’s credibility. The Common Framework, as currently structured, is thus not up to the debt challenges facing African countries.

Conclusion

To sum up, the international community provided much-needed liquidity and temporary debt- service relief to low-income countries during the pandemic. However, the DSSI and the Common Framework have not lived up to the international community’s professed level of ambition.

Africa therefore needs a permanent mechanism to help manage and resolve its debt crises. While there is no adequate international debt-resolution framework, there is nevertheless an urgent need to tackle the liquidity issues and insolvency risks that many African countries face.

To address excessive current debt burdens, as well as to prevent future distress in countries where debt is currently sustainable, African countries should act collectively to create a continental financial safety net. Africa is the only continent without a Regional Financing Arrangement to protect itself against shocks. 6

References

- African Development Bank [2022], African Economic Outlook. Supporting Climate Resilience and Just Energy Transition in Africa. AfDB, May 2022. Abidjan (Côte d’Ivoire).

- International Monetary Fund (IMF) Blog. December 2, [2021]. The G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments Must Be Stepped Up. Washington, DC (USA).

- IMF [2023], World Economic Outlook. IMF April 2023. Washington, DC (USA).

- M. A. Kose, F. Ohnsorge, C. M. Reinhart, and K. S. Rogoff. [2021]. The Aftermath of Debt Surges. NBER Working Paper 29266, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

- M. A. Kose, F. Ohnsorge, and N. Sugawara. [2021]. A Mountain of Debt: Navigating the Legacy of the Pandemic. Policy Research Working Paper 9800, World Bank, Washington, DC.

- World Bank. [2022]. Global Economic Prospects. January 2022. Washington, DC (USA): World Bank.

- World Bank, International Debt Statistics Database. Washington, DC (USA): World Bank.

————————-

1. On the positive side, maturities have lengthened for several local currency debt markets since 2010: some countries have issued local currency bonds at maturities greater than 15 years.

2. Various African oil producers have struggled with oil-backed deals with commodity traders, ending up in distress.

3. It took six years for Cameroon to reach the Completion Point. Chad was the last country to reach its Completion Point, in April 2015, nearly twenty years after the HIPC initiative was launched.

4. The DSSI delivered $6 billion of relief during 2020, and a further $7 billion in 2021.

5. Private lenders gave no debt relief. They did provide $90 billion of new loans, including $14 billion to DSSI countries.

6. RFAs include the Arab Monetary Fund, the BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement, Chiang-Mai Initiative Multilateralization, the Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development, the European Union’s Balance of Payments facility, the European Stability Mechanism, and the Latin American Reserve Fund. Appendix A summarizes them.

Learn more