October 30, 2023

In August 2021, as the world continued to grapple with the far-reaching effects of the ongoing global pandemic, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) took a significant step to help. Recognizing the unprecedented challenges faced by nations, the IMF issued an allocation of US$ 650 billion worth of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), the largest ever. This financial lifeline was designed to bolster countries in their fight against the pandemic’s economic repercussions. SDRs, a reserve asset of the IMF, were meant to alleviate the financial strain on nations, offering hope and assistance in the face of an unparalleled crisis. However, as this allocation was distributed based on member countries’ quotas at the IMF, most of the allocation was assigned to wealthier countries.

At the end of October 2021, recognizing the dire financial challenges faced by vulnerable nations, the G20—comprising the world’s major economies—pledged to recycle a significant sum, US$ 100 billion worth of SDRs. These SDRs, which had been received by the wealthiest nations in the August allocation and were idling within advanced economies’ central banks, were to be transferred to assist vulnerable countries in recovering from the economic turmoil and rebuilding their financial stability.

Today, the eve of the two-year mark of the G20’s initial commitment and after additional shocks like the Russian invasion of Ukraine, actual pledges still fall short of the promised $100 billion of SDRs by nearly $13 billion. More shocking is the fact that less than 1% of the promised support has found its way to the countries struggling on the margins of the global economy. In this blog, we delve into the present status of commitments, exploring the reasons why a significant portion of SDRs remains inaccessible to vulnerable nations. Furthermore, we urge advanced economies and their central banks, particularly the European Central Bank, to reconsider their stance and display greater ambition and speed in recycling SDRs via the multilateral development banks.

Where do we stand on SDR pledges?

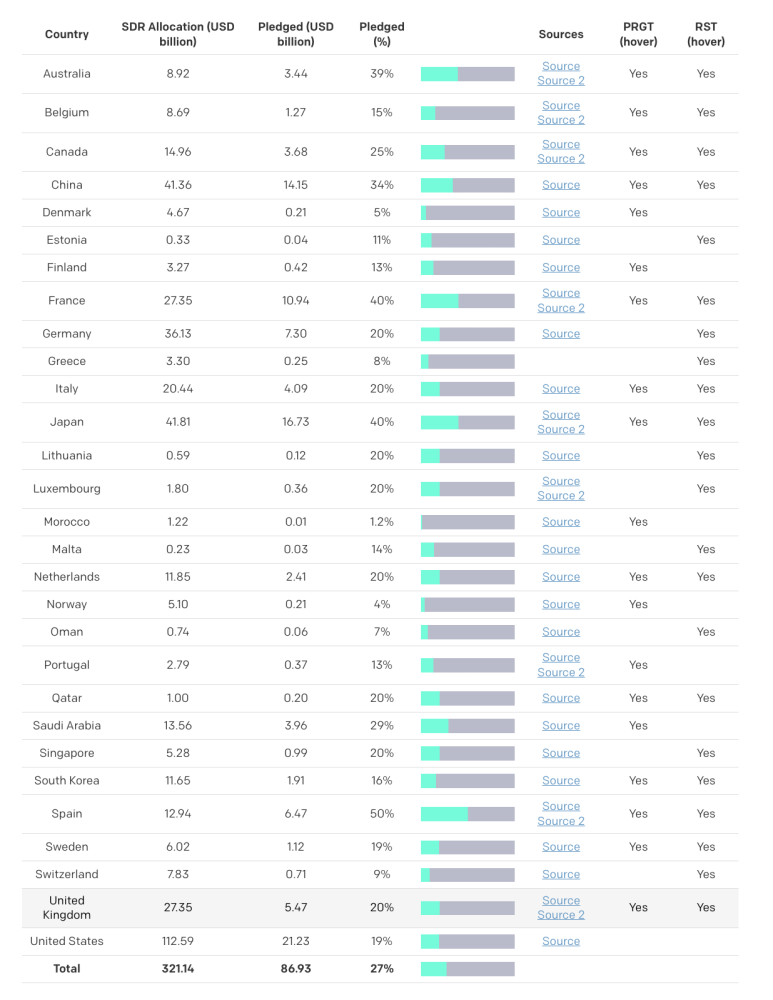

The ONE Campaign tracks publicly declared commitments, and the most recent update reveals that advanced countries have pledged a combined total of US$86.93 billion of SDRs, as indicated in the table below. The commitment sought to have each G20 member recycle 20 percent of their August 2021 SDR allocation. While several nations have exceeded this mark, including Australia, Canada, China, France, Japan, and Saudi Arabia, many countries are struggling to fulfill even 10 percent of this commitment (or not engaging at all). Notably, the United States faces a unique obstacle: “the recycling of SDRs must be approved by Congress, which thus far has left the Biden Administration’s request to recycle US$21.2 billion of SDRs stalled.

Some central banks have voiced reservations regarding the recycling of SDRs, particularly going beyond the 20 percent pledge, citing concerns about potential impacts on their foreign exchange reserves. However, as we highlighted in a recent blog post, while these concerns have their merit, the data reveals that existing recycling commitments do not significantly jeopardize the reserves of advanced countries; they can mitigate any potential impact.

Table 1. SDR recycling pledges

Source: The ONE Campaign’s “Special Drawing Rights” data dive. Accessed on 10th of October 2023

Why have more SDRs yet to reach vulnerable countries?

So, where do the US$ 87 billion of SDRs pledged for recycling currently reside? Remarkably, most of these SDRs continue to be held within the confines of advanced economies’ central banks or treasuries. Almost all pledges to recycle SDRs have been directed to two IMF trusts which make loans to vulnerable middle- and lower-income countries: the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT) and the Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST). We must acknowledge the IMF for its efforts in establishing and operationalizing the RST, approving more than ten programs, and initiating disbursements in less than two years. However, together, the PRGT and RST have disbursed only US$ 702 million of SDRs. So what is going on with the other US$ 81.3 billion?

Understanding why most of these SDRs continue to be held in advanced economies’ central banks requires a knowledge of the mechanism of these trusts. They do not hold loanable resources; instead, the loanable resources are retained in the central banks of the respective donor countries until the IMF approves a disbursement. This approval triggers a call to the central bank of the donor, requesting the release of the pledged SDRs. Such calls have taken place for recycled SDRs only once in the case of the PRGT and five times for the RST, amounting to less than 1 billion USD worth of SDRs disbursed so far.

It is also important to mention that although both trusts are similar in that they do not hold loanable resources directly, they differ in their financial structure. Without delving into specifics, it’s important to note that the PRGT has a financial model that allows for recycled SDRs to be credited to an investment account. This arrangement enables the IMF to invest these resources, generating subsidy resources, which ultimately facilitate lending under the PRGT at a 0 percent interest rate. On the other hand, the RST mandates a minimum of 20 percent of the promised loans to the RST to be held in the deposit account and a minimum of 2 percent in the reserve account. Both guarantee the smooth functioning of the trusts. The SDRs in these accounts have left the central banks of advanced economies.

According to the latest information contained in the IMF quarterly report on IMF finances, approximately US$ 12 billion worth of SDRs currently reside in the RST reserve and deposit accounts. However, it’s important to mention that determining whether these contributions are recycled SDRs is challenging, as contributions can also be made in hard currency. At best, US $ 13 billion worth of SDRs have been put to use, either by reaching vulnerable countries or by allowing the PRGT and RST to function efficiently.

What can G20 members do to speed up the effective recycling of SDRs?

As mentioned earlier, the recycled SDRs have been recycled only into the IMF trusts, which have reached their capacity and cannot accommodate additional SDRs, as we emphasized in a recent analysis. Present commitments within the RST only amount to less than 5 billion, scheduled to be disbursed over the next four years. Similarly, commitments within the PRGT are constrained by the availability of additional subsidy resources. This unfortunate reality implies that, at the current rate, it would take decades for vulnerable nations to receive the promised 100 billion worth of SDRs. Yet, these nations require immediate financial aid, making the delay in disbursement a matter of critical concern.

However, the IMF trusts should not be viewed as the sole avenue for recycled SDRs, as there exist alternative methods to expedite the disbursement of recycled SDRs to vulnerable countries. One promising approach is to recycle SDRs through multilateral development banks (MDBs), a solution we have explored extensively in past discussions. This approach can ensure efficient utilization of SDRs and significantly accelerate the recycling process. Nevertheless, certain constraints surround the potential recycling of SDRs, particularly in alignment with its reserve asset characteristic.

Advanced economies are hesitant to recycle SDRs to MDBs as they are worried that this would not preserve the reserve asset characteristic. Notably, the European Central Bank (ECB) has stated that recycling SDRs to MDBs is not permitted under current ECB rules and regulations. However, the IMF already made clear that SDRs recycled to MDBs will be counted as reserves by the IMF, and a recent study demonstrates that SDRs could be recycled to MDBs while meeting ECB rules and regulations. So now it’s time for advanced economies’ central banks to be more ambitious, as SDR recycling to MDBs is an excellent deal for donors, too.

The G20’s declaration that recycling targets have been met is dubious at best. Vulnerable countries have only received US$ 702 million of the intended US$ 100 billion. While the global community searches for vast amounts of money to support developing countries, they are overlooking a promise that, with the right political push, would be easy to keep and would get money in the coffers now.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Learn more