Implementing MDB Reforms: A Stocktake

April 11, 2024

Executive Summary

The challenges facing the developing world got steeper in 2023. About half of International Development Association (IDA)-eligible countries failed to recover to pre-pandemic income levels. Per capita growth was anemic: 0.7% in Africa, 0% in the Middle East, and 1.5% in Latin America, partly because of weak investment levels. Currently, gross investment in most emerging market and developing countries (EMDCs) barely covers the depreciation of the existing capital stock; investment rates are in the range of 20-25% of GDP in all regions except Asia, where the average investment rate is 38% of GDP. The consequence of such low investment rates is that EMDCs will be unable to transition to green economies, to adapt to already-present climate change, or to sustain rapid growth, with dire impact on their own populations and on the global efforts to reach net zero.

While the imperative is to accelerate sustainable investment, external financing for EMDCs has become expensive and harder to mobilise. Meeting the challenge of increasing investment requires a pipeline of high-quality, specific bankable projects, along with confidence that these can be implemented in a timely way. It also requires secure, predictable, and affordable finance to make the investment at reasonable cost. However, external financing for EMDCs became more expensive and harder to mobilize in 2023. The external debt servicing of EMDCs rose by $40 billion. Low-income countries were hit especially hard; the debt service ratio in sub-Saharan Africa rose from 21% in 2022 to 32% in 2023.

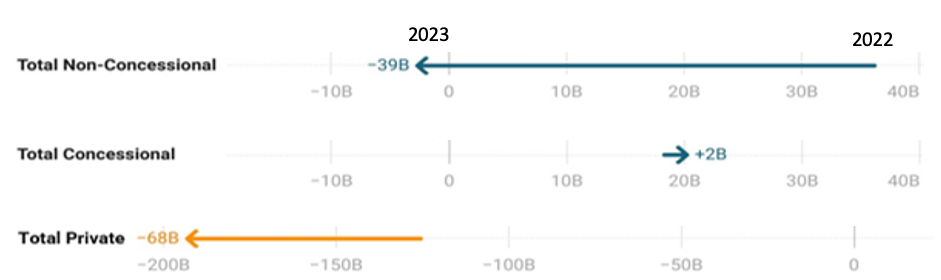

Support from international financial institutions and bilateral donor agencies was inadequate to fully offset negative private capital outflows. Nearly $200 billion was taken out of EMDCs (ex-China) by private creditors in interest and net repayments. And while the financing from multilateral institutions continued at record levels, aid flows were diverted to meet the rising costs of humanitarian crises, including the costs associated with refugees in donor countries, as well as for the war in Ukraine. As a result, programmable official development assistance (ODA) flows received by low-income countries fell even as total ODA rose.

Figure ES1: Capital outflows from developing countries intensified during 2023 (shown in billion US$)

It was in anticipation of these trends, and of the equally alarming prospects for the rest of the decade, that the Indian G20 presidency commissioned an Independent Expert Group (IEG) to propose an alternative path forward. In their reports of July and October 2023, the IEG identified a better, bolder, and bigger system of multilateral development banks (MDBs) as a key element of a global program to help EMDCs improve the investment climate, strengthen project pipeline development, and secure adequate levels of affordable finance. That vision envisaged a transformed MDB system that would lend three times more by 2030 and mobilize five times more private capital through a variety of new instruments and strategies. Equally importantly, the MDBs would broaden their mission and vision and play a central role in helping countries set up platforms for scaling up and speeding up investment programs in climate related and other global challenges.

The vision of better, bolder, and bigger banks was endorsed by the G20 leaders in the New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration. The IEG made recommendations to streamline, harmonize and speed up MDB procedures, to promote more risk taking, and to mobilize additional capital through traditional and innovative means. Subsequent international gatherings have reiterated political support for the transformed MDB agenda, including the Paris Pact for People and Planet and the UAE Climate Finance Framework launched at COP28. The Brazilian G20 presidency has made the development of a roadmap for “better, bigger, and more effective MDBs” a central plank of its priorities for 2024. Alongside the political support, the leaders of MDBs have also welcomed the ambitious agenda set out in the IEG reports.

All MDBs have launched programs to begin implementing the various components of the broader reform agenda. As detailed in an MDB Reform Tracker, they have incorporated global challenges into mission statements and advanced the capital efficiency agenda.

Notwithstanding these developments, the pace of MDB reforms remains inadequate to have a material impact on sustainable development. Our assessment is buttressed by the results of a survey of international experts, who remain skeptical that there is enough momentum to implement sufficiently deep reforms across key areas.

We have identified five areas where progress appears slower than what was proposed in the IEG reports and where substantial acceleration and increased ambition in the current pace of implementation is required.[1]

We urge Ministers to encourage MDB managements to make a credible push on these in 2024, starting with their deliberations at the IMF/World Bank Spring Meetings.

- Roll out proactive and disciplined engagement with Country Platforms to help deliver scaled up investment programs. All stakeholders urgently need to come together behind country-led strategies and plans for scaling up investments in a balanced program to address climate change and meet other development goals. Some countries like Brazil, Barbados, Egypt, and the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) countries are coming forward with such plans, and more need to. The submission of the next round of nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and the preparation of prosperity plans by Vulnerable Twenty (V20) countries provide a good opportunity for setting out actionable investment and financing programs that integrate climate and development needs in shared country platforms that combine specific projects with regulatory and business climate reforms. MDBs committed to play a central role in supporting such country platforms, in the joint COP28 Statement, but without any specific targets or timelines.[2]

- Enhance efforts to mobilize private sector capital flows (PCM) to EMDCs. Only ADB, IDB and EBRD have set explicit PCM target ratios. Other MDBs should emulate this. MDBs are swimming against the tide in trying to reverse private capital outflows. They have learned that subsidies deployed through blended finance, even at scale as in the IDA private sector window (PSW), are not sufficient to overcome internal MDB barriers to taking on more risk and expanding pipelines in difficult environments. Addressing these internal barriers has started in some areas, as in the World Bank’s consolidation and rationalization of its guarantee offerings, but there is a long way to go in other areas such as building whole-of-bank approaches that combine support for reducing risk with tools to share risk. This may be the biggest management challenge confronting MDB leadership.

- Conclude the replenishments of IDA and ADF at a scale commensurate with the needs of low-income countries. We estimate that IDA-eligible countries would need incremental external financing of $350 billion per year by 2030 to make a material impact on sustainable development. The implication is that concessional financing for key investments should reach almost $200 billion per year by 2030. This scale should frame the ambition for substantial replenishment of IDA21 and ADF14.

- Go further on MDB balance sheet optimization, including by better valuation of callable capital. MDB Heads have indicated they have identified capital adequacy framework (CAF) measures that could potentially add up to $30-40 billion per year for a decade by 2030. This is in line with expectations in the IEG report, based on the CAF review. Much remains to be done to realize the potential, including on callable capital, further movements on the equity-to-loans (E/L) ratio, and sale of MDB assets.

- Expand MDB lending capacity by mobilizing hybrid capital and portfolio guarantees, and by recognizing the medium-term need for a capital increase. The African Development Bank’s (AfDB’s) successful issuance of hybrid capital could have an important demonstration effect. Other MDBs should accelerate plans to issue similar instruments to private and public investors and standardize offerings to build the asset class. Several MDBs have also begun to mobilize guarantees from shareholders with high credit rating to cover specific risks to their loan portfolios, but the scale and coverage can be greatly expanded. The proposed 2025 shareholder review to align capital resources with ambition in the World Bank Group is welcome. Similar reviews could take place in other MDBs, where warranted.

While there is room to disagree on whether the glass of MDB reform is half-full or half-empty, what is important is the size of the glass. Our overall assessment is that the glass is still much too small. Our metrics of reforms suggest that there is undeniable activity, but that impact is falling short of what is required. A few green shoots offer potential for scaling in the five key areas listed above. The IMF/World Bank Spring Meetings should send signals that these shoots and other measures will grow fast.

2023 will be remembered as a year when the global community recognized the need for ambition and urgency in getting developing countries on track to meet sustainable development, climate, and biodiversity goals.

2024 needs to be the year when initial implementation of the reform agenda provides credible assurance that this vision will be realized. Our current assessment is that such an assurance would require a substantial stepping up of the pace and scope of ongoing actions both by the MDBs themselves and by their shareholders.

[1] We recognize that the geopolitical context and the calendar of near-term elections in many G20 members make major reform initiatives difficult. But against this we need to weigh the consequences of inadequate implementation – further erosion of trust in multilateral action and surging costs of delay in development and climate outcomes that will be no easier to pay after the delay.

[2] Some of the regional development banks are taking the lead. For example, the ADB’s experience in supporting scaled country platforms could provide lessons for other MDBs still struggling with these financing channels.

To see the full note click the Learn more link below.