Loan Repayment in Poor Countries: Myth-Busting New Evidence from MDBs and DFIs

March 28, 2024

For those of us who have long been pressing for more access to data from the Global Emerging Markets (GEMs) Risk Database (here and here), the publication this week of a report on MDB loan recovery statistics is welcome validation of the market-building importance of these data and an important step towards more regular and robust disclosure.

The new report

GEMs data show the probability of default and losses given default for loans to developing countries from 25 MDBs and DFIs. The database includes twenty thousand transactions stretching over more than three decades: the GEMs website itself bills it as “one of the world’s largest credit risk databases for the emerging markets operations of its member institutions, that are Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and Development Finance Institutions (DFIs).” The data include credits to governments and to the private sector. But only the members of the GEMs consortium, the participating MDBs and DFIs, can access the data.

In response to ongoing external demand for access, GEMS issued two highly aggregated reports on loan default rates in 2023. This new report focuses on the shares of loans in default that are recovered by (i.e., repaid to) MDBs and DFIs. It is obviously a useful tool for strengthening risk assessment, especially risks for transactions in which MDBs are participants.

It covers one key dimension of the picture: recovery rates for loans to private and sub-sovereign borrowers made over the period 1994-2022 that were in default. Default is defined as payment arrears, loan write-offs, distressed restructurings, borrower bankruptcies, or other events negatively impacting repayment. Recovery rates are defined as the ratio between the discounted cash flows received (or expected) and the outstanding amount of default. For the first time, the data allow us to compare recovery rates by region and by country income group.

There is no breakdown by sectors, but the report does separate infrastructure and financial services. Remaining sectors are put in a catch-all “other” category.

As you can imagine, private lenders, MDB shareholders, credit rating agencies, development finance analysts, and other MDB/DFI stakeholders are all interested in what the data show about the creditworthiness of private borrowers in emerging markets and developing economies. MDBs themselves have an interest in demonstrating the value of what is termed the “halo effect”: the expectations of superior repayment track records in private finance transactions where MDBs participate. We have long suspected that releasing more data would surprise people who make unfounded assumptions about loan repayment track records in poorer countries. And that is exactly what this report does.

Probably not what you expected

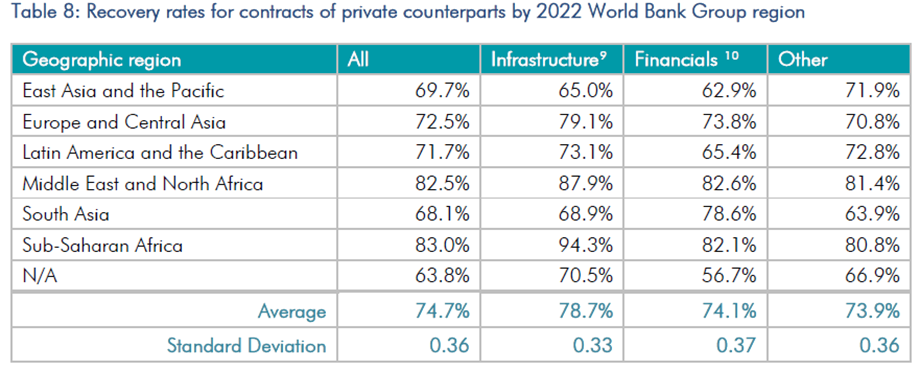

Table 8 from the report should be a wake-up call to those who accept and act on regional stereotypes about risks of lending to the private sector. In the absence of evidence, many lenders assume that sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) are the regions of highest risk. These data show in fact that those two regions consistently have the highest recovery rates across the three highly aggregated sectors the report uses.

Source: GEMS, 2024.

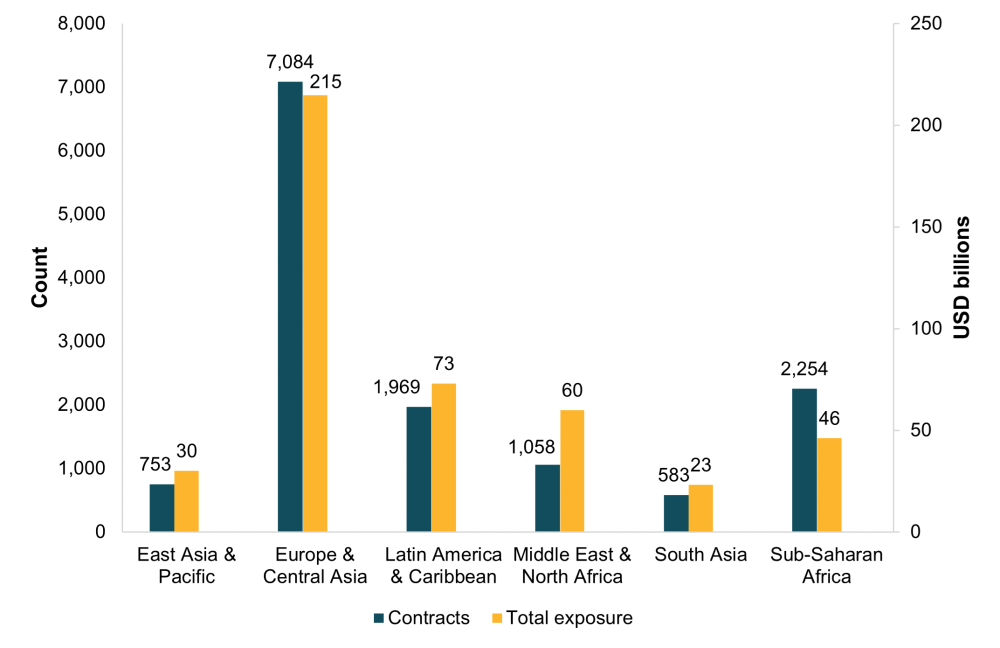

Some would suggest that this is a function of the smaller number of projects financed: tougher investment climates and more difficult project due diligence result in fewer transactions for these regions that can make it through MDB/DFI credit committees. The data do not support this explanation, as Figure 1 shows. SSA has the third highest number of transactions of any region, and the MENA region has more transactions than East Asia and the Pacific.

Figure 1. Transactions with private and sub-sovereign counterparts, 1994-2022

Source: GEMs, 2024.

Note: Total exposure figures were converted from euros using exchange rate at time of writing.

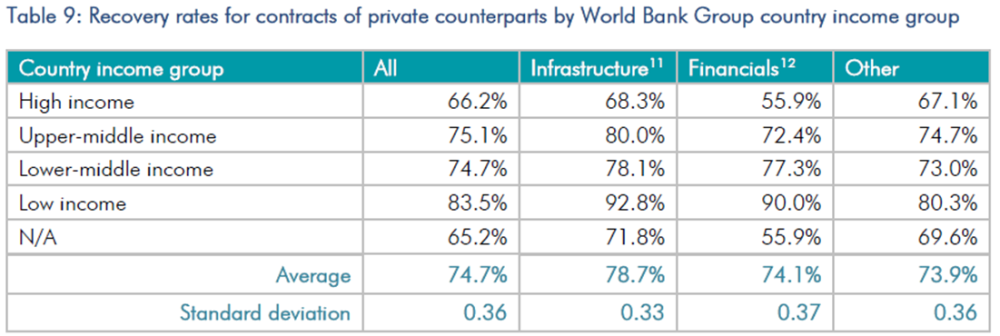

Table 9 from the report also explodes conventional wisdom. Recovery rates for the poorest countries—the low-income country group in the table below—are considerably higher than those of other regions and higher than the average across regions.

Source: GEMs, 2024.

Much has been written about how hard it is for MDBs and DFIs to find bankable projects in the private sector in the poorest countries. Many assert that MDBs and DFIs interested in mobilization of private finance should instead focus their efforts on middle-income countries (MICs). What this—admittedly very partial—evidence suggests is that for loans in default, the risk of losses is actually lower in the poorest countries than in MICs. More insights could be gained if we could compare recovery data with default rates by income level and region, but unfortunately the GEMs publications on default rates do not provide these breakdowns.

What we still don’t know

What is not in this report? It does not include updated data on the probability of default in the first place, as distinct from how much is recovered in the event of default. We understand GEMs will report updated default data in a future report. It also does not include a sectoral disaggregation more specific (and useful) than the three-part division of “infrastructure,” “financials”, and “other”. And the report does not disaggregate by country, just by region. More disaggregation is essential to help private lenders and credit rating agencies make evidence-based, differentiated risk assessments rather than lowest-common-denominator assessments.

Critically, stakeholders should not have to wait for infrequent, ad-hoc reports to access these data. As has been stressed by the G20, the core objective is a stand-alone, publicly accessible database.

Care must clearly be taken not to disclose business confidential information about individual transactions that are protected by non-disclosure agreements, which is one rationale for not disclosing more disaggregated data. But this challenge can be overcome by deploying a database tagging process that removes data points from reporting in cases where publishing data from a small number of transactions in a given sector and/or in a given country would reveal information on specific transactions. That would be desirable in any case as one would not want to judge risk based on too small a sample size.

There are of course resource costs associated with setting up a public database, including scrubbing the database for accuracy, harmonizing definitions and measurement across MDBs and DFIs, regularly updating the data, ensuring that transaction parties are anonymized, and avoiding other disclosure of business confidential information. We have heard much about these costs for many years, but a consortium with 25 members ought to be able to fund these costs through reasonable membership fees scaled to take into account relative budgets. Shareholders, by stressing their interest in more GEMS data transparency, have signaled their willingness to approve funding for a GEMs database. More importantly, these budget costs must be weighed against the less easily measurable—but equally real—costs of inaccurate risk assessments, distorted by gaps in information, that thwart investment and market development.

How much disaggregation is enough?

In deciding the right balance for these risks and costs, an understanding of what information has the most impact on private lending decisions is critical. Not all credit performance detail is needed or useful. It is important to identify the kinds of data and levels of disaggregation that are most important for filling critical gaps in information. Notably, the MDB Challenge Fund has provided a grant to the International Finance Corporation to carry out a market study for this purpose, the results of which will be made public.

We also recommend a second source of guidance: include GEMs on the agenda of the World Bank’s new Private Sector Investment Lab. The Lab is a group of prominent CEOs charged with recommending new approaches, products, initiatives, and processes to drive major improvements in World Bank private finance performance. Their input on what credit assessment gaps are most important to fill could go a long way to moving this initiative forward.

Just the beginning?

We commend the GEMs consortium for producing this report. The analysis yields important market-building information from transactions partially funded by public institutions. It demonstrates that the attention that has been focused on GEMs data in reports to the G20 (see here and here) and elsewhere is justified.

We very much hope that this report is a first step on the road to greater openness and transparency. We understand that another report planned for this fall will include updated default and recovery rates, hopefully on a considerably more disaggregated basis and as a prelude to access to a well-constructed database. This is a critical year for decisions by MDB management and their shareholders, as well as DFIs, about how much information value will be extracted from the unique asset that is GEMs.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Learn more