Reformed MDBs for a Just Energy Transition in Emerging Economies

June 13, 2023

Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) are potentially an important source of finance for low-carbon transition pathways and just transition in the emerging economies. However, there is increasing concern among the developing countries that MDBs are unable to mobilise adequate finance to be in line with the global goals. The G20 injected a huge momentum towards reforming MDBs’ operations by commissioning an independent review of their Capital Adequacy Framework (CAF), which primarily defines their capacity to leverage shareholder’s capital contribution for financing. While various risk-sharing tools have been used by MDBs, the frequency of use of such tools, for example, ‘guarantees’, represent a minor share in their portfolio. This warrants the question of whether MDBs have the appetite to take up risk-sharing more aggressively and if that would require changing their existing business models and operation strategies. This Policy Brief seeks to address the challenge of MDB reform amidst the financing gap for just energy transition in emerging economies, and suggest policy recommendations for the G20 to push this agenda in India’s presidency.

1. The Challenge

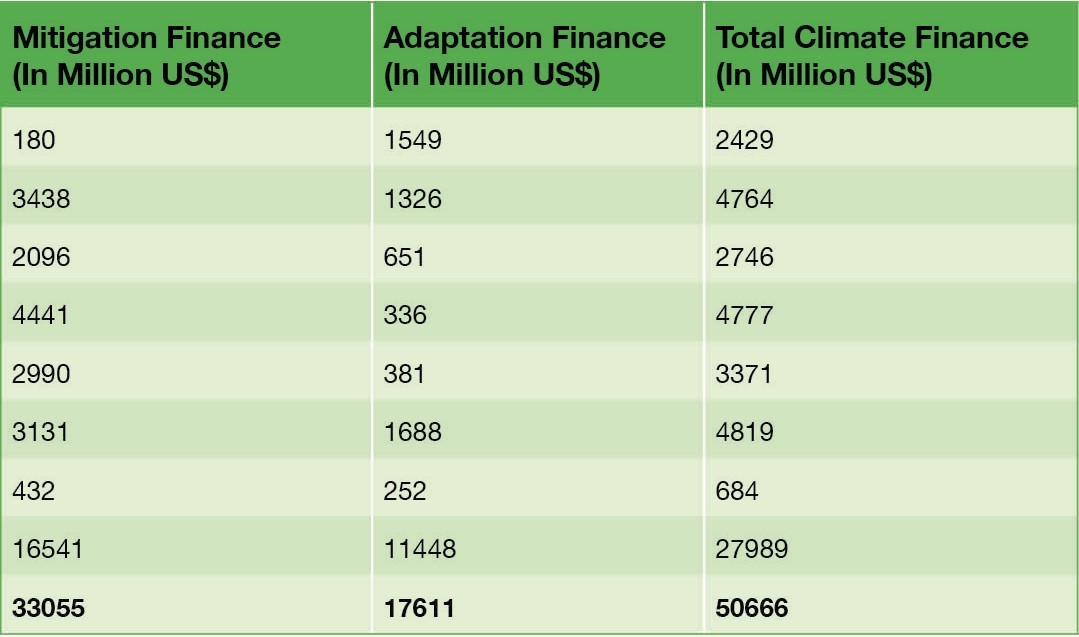

The Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) have committed to expand support for developing countries towards the 2015 Paris Agreement goals.[1] All MDBs have committed to enhance their leading capacities by at least 30-40 percent purely towards climate action projects in the coming years. The MDBs provided approximately US$51 billion of climate finance to low- and middle-income countries in 2021.[2] MDBs can mobilise resources at scale because they can raise cheap finance from the capital markets primarily due to their preferential creditor treatment and backup from member governments.[3] Table 1 shows the amount of climate finance mobilised in 2021 by MDBs for adaptation and mitigation.

Table 1: Climate Finance Mobilised by MDBs in FY2021

Source: MDB joint report, 2021[4]

The magnitude of the finance required for climate action is huge, and the role of the MDBs is critical. Existing studies highlight that the transformation of the global economy needed to achieve the net-zero goals by 2050 will be universal and significant, amounting to US$9.2 trillion in annual average spending on physical assets, which is US$3.5 trillion more than today.[5] At present, the global GDP is approximately US$70 trillion with global savings of US$20 trillion. This portrays a grim picture of the finance currently available and there is a need for innovative ways to leverage more capital through a multi-stakeholder approach. The challenge of mobilising finance further escalates with the ‘Just Transition’ discourse particularly in emerging economies as there are many first- and second-order effects associated with the transition. Not only is the transition to clean technologies capital-intensive, but finding alternative jobs for the fossil-fuel-based workforce increases the financing requirement significantly. For example, a study has estimated that India will require US$900 billion for a just energy transition vis-à-vis coal mines and thermal power plants over the next 30 years.[6]

The MDBs have already set out plans to incorporate just-transition-based projects in their portfolios in the years to come. Transition to renewables is already a lucrative option for MDBs because of the high returns.[7] However, to ensure the transition is just, capacity-building at the grassroots becomes critical, and adaptation-based projects therefore need to be prioritised at par with mitigation projects in the future. Moreover, the donor contributions to the MDBs’ concessional window have been saturating and as a result, the MDBs’ financing headroom could narrow. The combined effect of tightening of financial conditions and member governments’ hesitation to increase the capital base can further narrow MDBs’ financing space.[8]

2. The G20’s Role

Climate change has catastrophic effects, leading to a substantial financial burden globally and the impacts have mostly been suffered by the emerging and low-income economies. These economies historically have been the primary borrowers of development aid from MDBs.[9] Considering the already existing financial burden of these countries towards developmental challenges, climate issues have escalated that burden significantly and made these countries dependent on multilateral aid. Table 1 shows that the MDBs mobilised US$51 billion of climate finance in 2021, which is nowhere close to the amount required for global climate action. The finances mobilised by MDBs when compared to the total global finance mobilised—which is estimated at US$632 billion[10] —is less than expected. The reform debate in the emerging economies has started with the fundamental notion that MDBs have been formed primarily to provide developmental aid, and therefore to shore up the global climate finance requirements, there is a need to change the operation strategies and business models of the MDBs.

As mentioned earlier, all MDBs have committed to operating in line with the Paris Agreement. They, however, still have projects in the pipeline that indicate their investment plan towards enhancing fossil fuel uptake, particularly in emerging economies.[11] The alignment of tracking methodologies with the Paris Agreement is mainly towards their direct investment which leaves immense scope to align their indirect investments to identify the finance gap. An independent review of the MDBs’ Capital Adequacy Framework (CAF) commissioned by the Italian G20 presidency calls for MDB reform.[12] The Sharm-El Shiekh’s implementation plan which has been signed by 193 parties (including the G20 members) in the COP27 last year, called on the MDBs to reform their practices and introduce non-debt instruments to reduce the debt burden for the emerging and low-income countries.[13]

Therefore, the political discourse that MDBs have highlighted at multiple public forums, is the challenge of regional integration. The G20 has a huge role to play in eliminating the political barriers to such an arrangement. The pathway for MDB reforms, however, is not easy. MDBs have a set way of operating and sourcing their money, which mostly comes from the membership and their ability to borrow from the market. The pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war have had devastating implications on global savings. The global economy at present is in a state of high inflation where there is not enough scope to borrow from the market for long-term finance.[14] As a result, the risk of investment looms large for the MDBs. Furthermore, a parallel set of debates around MDB reform is that considering the urgency of mobilising additional finance, there is a need to operate outside their routine business models. For example, one of the success stories of the Glasgow Climate Summit is the announcement of the Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) with South Africa. The JETPs are nascent financing cooperation mechanisms aimed to support heavily fossil-fuel-dependent emerging economies towards a just energy transition pathway. In that regard, MDBs can mobilise funds towards JETPs, considering their financial capabilities, technical and local expertise, and development mandate.

It is imperative for this year’s Indian G20 presidency to find solutions and push the agenda of MDB reform. The unique nature of the G20, i.e., members comprising of both shareholders and borrowers of MDBs, will be key in pursuing the reform agenda. The G20 could act as a forum to improve diplomatic relations between countries so that MDBs gain confidence to enhance their lending capacity. Considering the magnitude of financing required towards climate action and just transitions, this Policy Brief outlines pertinent recommendations towards MDB reform, which the G20 as a unique platform can push into their agenda.

3. Recommendations to the G20

- Increase the capital base for the MDBs: The Capital Adequacy Framework (CAF) independent assessment advocates equating callable capital with paid-in capital. This is not an ideal plan since it will muddle the duties and responsibilities of two different kinds of capital, each of which is unique in its own manner. While paid-in capital safeguards the general operation of MDBs as ongoing organisations, the system of MDB leverage, the budgets of shareholder governments, and callable capital safeguards the bondholders.[15] Therefore, the viable option that should be on top of the MDB reform list is to protect paid-in capital to lend more funds. Funds from the Bretton Woods institutions, in particular the International Monetary Fund (IMF), could be available for the MDBs for lending or as capital or the IMF could serve as the last resort for the MDBs. Studies have shown that the methodology used by the credit agencies have led to a chilling effect where the MDBs have reduced their financial exposure more than needed to get a good credit rating.[16] This is because multiple credit rating agencies use different methodologies which often over-estimate the financial risks faced by the MDBs. This issue has been highlighted by the G20 before; concrete actions have yet to be taken as a response. This year’s G20 presidency can push for the credit agencies to come together and formulate a single methodology that will not overestimate the financial risks, and push the MDBs to take more risks without thinking about their credit ratings.

- Tapping in Private Investment: Tapping into greater amounts of private finance will be one of the key areas of MDB reform. An OECD report published in 2020 observed how MDBs have mobilised 69 percent of global private finance between 2018 and 2020.[17] Though this is a considerable amount of private finance, the ticket size for climate-related investments remains small and at best, medium. Therefore, MDB reform should envisage innovative de-risking measures to tap into private capital. The key is to create an investment-friendly environment for easy on-boarding of private players.The investment-friendly opportunities will come through development of standardised and innovative solutions to reduce the transaction costs for private investments by creating a pipeline of commercially viable and bankable projects. A synergised mitigation and adaptation project will regain investor confidence as the mitigation component usually ensures a guarantee of return. MDB reform needs to ensure that the mobilisation of private finance at scale towards climate action should be at an institutional level.The International Finance Corporation (IFC) is the only institution to date with a specific mobilisation aim, and with just US$10.8 billion in private and public financing raised in the fiscal year 2020, it fell short of its own US$11-billion target. A structured partnership between the public and private arms of the MDBs can increase private finance mobilisation. This is essential for identifying and reducing sector-specific investment risks, such as institutional and policy restrictions that diminish the number of projects that are bankable and investible.The MDBs can also issue a greater number of innovative financial instruments like green and blue bonds, and sustainability-linked bonds, to tap into more private players. The Asian Development Bank (ADB), for example, has formulated a ‘Green and Blue Bond’ framework which aims to develop a global green bond market. The ADB has issued approximately US$10.0 billion equivalent in green bonds since 2015.[18] This framework can be replicated across all MDBs to support its developing member countries to be in line with their climate commitments. They can also enhance Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) and bridge the two sectors, enhancing the access to new and innovative financial instruments. This then becomes a trustworthy investment scenario for the private players.

- Change in MDB’s operation strategy: The MDB management and shareholders should announce plans and explore new financial and policy incentives for countries to better access finance. This will require a change in their terms of lending, which will include providing concessional grant-based finance especially to emerging and low-income economies that can be deployed through multilateral pool funding. This will then entail longer repayment options and provide some flexibility for these countries. Additionally, MDBs must act as guarantors by updating the guarantee provisional regulations and enhancing employee training programs and incentives for non-lending items. Moreover, to increase their lending capacity and use their existing financial headroom, it will be ideal to invest in projects with well-defined development and climate synergies. There is ample research that illustrates that such projects are far more financially rewarding from an investment perspective. The MDBs also need to have a clear demarcation of what climate projects entail through certain indicators that will help them track the finance being mobilised.

- Aligning the MDB trust funds towards mitigation and adaptation actions: The number of climate-related trust funds have increased significantly following the Paris Agreement. The MDBs depend highly on these funds to enhance their lending capacity and over the years have developed more than 200 such funds.[19] These have also been bifurcated with designated adaptation and mitigation funds. Some studies have, however, empirically illustrated[20] that these funds have a singular resource allocation criteria which is problematic as the allocation of the trust funds must cater to country-specific needs. This is an important element of MDB reform.It has been observed that trust funds with a focus on mitigation, generally allocate aid in line with efficiency considerations. However, trust funds with a focus on adaptation do not seem to prioritise countries with the maximum need.[21] In the context of just transition, adaption interventions are interlinked with mainstreaming the deployment of renewables as alternative sources of energy. Moreover, there is a need for the MDBs to allocate more capital in the adaptation trust funds which is far less than the mitigation trust funds. The MDBs also need to be transparent in sharing information regarding these trust funds at public forums to better understand their allocation patterns.

- Reduce the foreign exchange currency risk: Countries can borrow in foreign currency at a cheap rate but the key issue is foreign exchange risk, country political risks and country risks. Moreover, the high cost of hedging and the absence of a long-term hedging market exposes projects to a currency risk in the medium or long-term. The problem escalates as the repayment obligations are in US Dollars whereas the revenues are in local currencies. The need to reduce foreign exchange risk has been acknowledged, though nothing concrete has been done so far. One potential solution can be formulating an ‘International Foreign Exchange Agency’ that could operate on an international platform to lower the cost of foreign exchange hedging in developing countries for green projects.[22] Considering the geopolitical hold of the MDBs in the present world order, they can come together in becoming a secretariat for such a platform in which the World Bank might be the lead implementing and regulatory body.The Indian G20 presidency has a huge role to play by pushing this agenda by laying a groundwork for an international institutional arrangement to help mobilise climate funds, especially for emerging economies. There are also discussions about extending the fiscal space of developing countries mainly through rechannelling the Special Drawing Right (SDR). The most obvious choice to re-channel SDRs is the IMF. MDBs, however, present another potential channel for reallocating SDRs to support developing countries provided some measures are taken to preserve their reserve asset nature.[23] A recent study has illustrated that there can be two forms of rechannelling SDRs through the MDBs, i.e., on-lending schemes and capital injections. The challenge of foreign exchange risk remains as the hard currencies that can be exchanged to get the SDRs are limited to only five till date.[24] Thus, the formulation of the ‘International Foreign Exchange Agency’ will help reduce the foreign exchange risk if MDBs channel SDRs.

- Form a MDB-wide technical committee on climate change: The reform will require a change in the operations and business model of MDBs. It is therefore necessary to enhance internal capacity-building through a collaborative initiative across all registered MDBs. An annual report jointly formulated by all the MDBs takes stock of the amount of climate finance mobilised for mitigation and adaptation actions.[25] Though the MDBs operate in a close-knit space, there is a need to go beyond and form a working group across the MDBs to discuss pertinent issues regarding enhancing the lending capacity particularly for climate action through understanding best practices internally across all the MDBs. The operationalisation of such a working group can be proposed in this year’s G20 presidency. It is also crucial that such a working group has beneficiary representation as Chairs to account for specific challenges. For example, if there is a large-scale project being developed in the African continent, there has to be a Chair representing that geographical location.

- Working outside the MDB architecture: As highlighted above, there is scope for the MDBs to work outside their business model. This will be a similar structure to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) where the MDBs lend money or are in an arrangement outside their routine operation regime. An example of this is the Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) where MDBs can on-board a partnership arrangement. They need to engage with other shareholders as well as partner countries and offer their expertise to negotiate successful partnerships. There are already talks in this year’s spring meetings of the World Bank, IMF and Center for Global Development (CGD) to host a side event and discuss the role of MDBs in existing and upcoming JETPs. There is also scope for MDBs to increase corporate sector collaboration with domestic funding and enterprises by tapping into their resources.

[1] Ayse Kaya, “Multilateral Development Banks and Climate Finance: More Words Than Action,” IISD/SDG Knowledge Hub, November 9, 2022.

[2] European Investment Bank, “JOINT REPORT ON MULTILATERAL DEVELOPMENT BANK’S CLIMATE FINANCE,” June 2021, Luxembourg, 2021.

[4] European Investment Bank, “JOINT REPORT ON MULTILATERAL DEVELOPMENT BANK’S CLIMATE FINANCE,” June 2021, Luxembourg, The European Investment Bank, 2021.

[5] Paul Donovon, “Finance in Revolutionary Times” April 2023, London, The Capco Institute, 2023.

[6] Bhushan, Chandra, Srestha Banerjee, and Shruti Agarwal. “Just Transition in India: An inquiry into the challenges and opportunities for a post-coal future.” (2020).

[7] Asian Development Bank, “MDB Just Transition High-Level Principles” June 2021, Manila, Asian Development Bank, 2021,

[8] David Andrews, “Reallocating SDRs to Multilateral Development Banks or other Prescribed Holders of SDRs,” October 2021, Washington DC, Center for Global Development, 2021.

[9] Ayse Kaya, “Multilateral Development Banks and Climate Finance: More Words Than Action,” IISD/SDG Knowledge Hub, November 9, 2022.

[10] Barbara Buchner et al., “Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2021”, December 2021, San Francisco, Climate Policy Initiative, 2021.

[11] Carolyn Neunuebel et al., “The Good, the Bad and the Urgent: MDB Climate Finance in 2021,” World Resources Institute, November 11, 2022.

[12] Johannes F Linn, “Expand multilateral development bank financing, but do it the right way,” Brookings Institution, 2022.

[13] Nandi, Jayashree. “MDB reform to scale up climate finance to developing nations to be discussed at G20.” Hindustan Times, December 01, 2022.

[14] Nandi, Jayashree. “MDB reform to scale up climate finance to developing nations to be discussed at G20.” Hindustan Times, December 01, 2022.

[15] Johannes F Linn, “Expand multilateral development bank financing, but do it the right way,” Brookings Institution, 2022.

[16] Anja C. Gebel, “Multilateral Development Banks Must Deliver on Climate” July 2022, Germanwatch Policy Brief.

[17] OECD, “Climate Finance and the USD 100 Billion Goal,” September 2022, Paris, OECD, 2022.

[18] Asian Development Bank, “GREEN AND BLUE BOND FRAMEWORK,” July 2022, Manila, Asian Development Bank, 2022.

[19] Michaelowa, Katharina, Axel Michaelowa, Bernhard Reinsberg, and Igor Shishlov. “Do multilateral development bank trust funds allocate climate finance efficiently?.” Sustainability 12, no. 14 (2020): 5529.

[20] Reinsberg, Bernhard, Igor Shishlov, Katharina Michaelowa, and Axel Michaelowa. “Climate change-related trust funds at the multilateral development banks.” (2020).

[21] Michaelowa, Katharina, Axel Michaelowa, Bernhard Reinsberg, and Igor Shishlov. “Do multilateral development bank trust funds allocate climate finance efficiently?.” Sustainability 12, no. 14 (2020): 5529.

[22] Puri, Manjeev, “Build a new global agency to push climate financing,” Hindustan Times, March 16, 2023.

[23] David Andrews, “Reallocating SDRs to Multilateral Development Banks or other Prescribed Holders of SDRs,” October 2021, Washington DC, Center for Global Development, 2021.

[24] David Andrews, “Reallocating SDRs to Multilateral Development Banks or other Prescribed Holders of SDRs,” October 2021, Washington DC, Center for Global Development, 2021.

[25] European Investment Bank, “JOINT REPORT ON MULTILATERAL DEVELOPMENT BANK’S CLIMATE FINANCE,” June 2021, Luxembourg, European Investment Bank, 2021.

Learn more